ELLO

City of Gunsmiths

Introduction to the missaglia

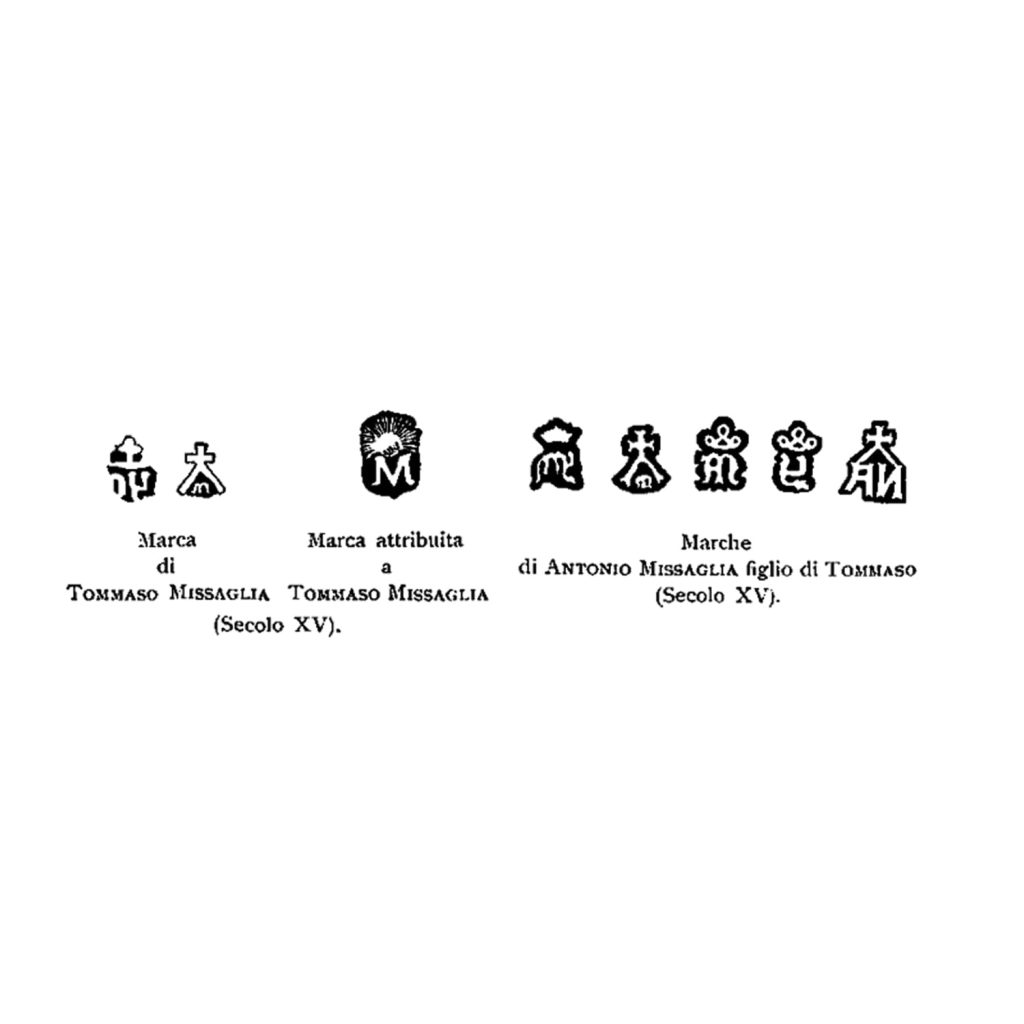

The Negroni, originally from Ello and perhaps better known as “Missaglia,” were among the most renowned armorers active in Milan between the 15th and 16th centuries. Their works were sought after throughout Europe, from the Milanese court of the Sforza family to the French royal court.

There is little certain information about Pietro Negroni, the family’s progenitor, who died in 1428. His son Tommaso was the first to be nicknamed “Missaglia,” a surname that likely derives from the parish to which the village of Ello originally belonged.

Tommaso greatly expanded the family business so that in 1450, the Duke of Milan, Francesco Sforza, appointed him and his son Antonio as ducal armorers, exempting them from paying taxes. Tommaso died in 1452, and Antonio, born around 1415, took over the family business. Under Antonio, the workshop reached the highest levels of fame and prestige. Ducal favor contributed to the expansion of their clientele, which, in the second half of the 15th century, included some of the most important Italian courts, such as Mantua and Ferrara.

Even from these few lines, one can sense how highly sought after the works of the Negroni family from Ello were. Their main clients included Francesco I Sforza, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Ludovico Sforza known as “Il Moro,” Ascanio Maria Sforza Visconti, King Louis XI of France, the condottiero Roberto Sanseverino, and many others.

During the Renaissance, Brianza was a land rich in armorers. In addition to the Negroni, other families active in this field included the brothers from Merate, Francesco da Vedano, Francesco Besana, Giovan Giacomo da Vimercate, Galeazzo da Verderio, Giovan Pietro Bernareggio, Ambrogio da Binago, Anselmino da Seregno, Bonaventura da Lissone, Giovan Ambrogio Varedo, Pietro da Desio, and Dionigi da Viganò.

Ello, Village of the Missaglia

Mantegna's Saint George

The Houses of

the Missaglia

The Missaglia and

Galeazzo Maria Sforza

Bramante's

Men-at-Arms

The Missaglia and

Ludovico il Moro

The Brera Altarpiece by

Piero della Francesca

The Various

Renaissance Armors

The Missaglia

Armors in Mantua

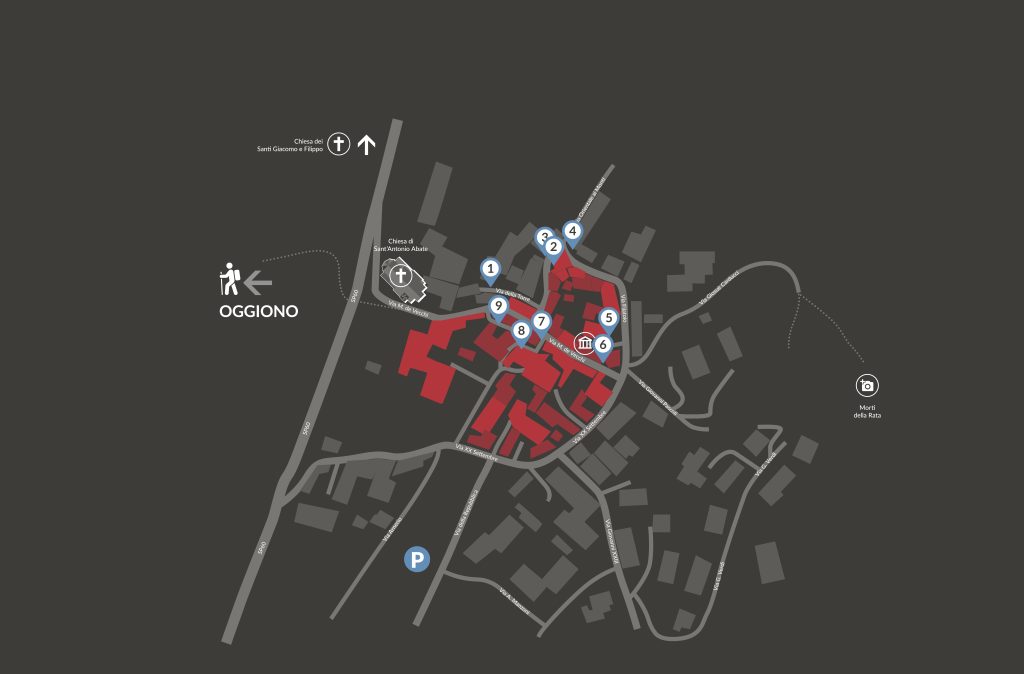

ELLO, VILLAGE OF THE MISSAGLIA

BOTTEGA DEI MISSAGLIA, HELMET, CA. 1475, NEW YORK, METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

The village of Ello has been inhabited since the Bronze Age, and its relationship with metals has always been significant. According to some sources, several iron objects dating back to the 2nd millennium B.C. were found near a stone quarry close to the village.

There was also a mine in the area which, according to experts, was used in ancient times as a weapon depot by itinerant blacksmiths.

In addition to the presence of metals in the area, water is also important for the development of the village of Ello. In particular, besides being fundamental in modern times for the development of the village’s spinning mill, it is also a basic tool in metallurgy. Water is essential for the operation of the hammer, a large hydraulically driven hammer used in forging and stamping metal.

Regarding the importance of water, it is worth noting the episode in which the Duke of Milan, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, gave Antonio Missaglia several hammers located in the Martesana and Navigli areas so that he could work iron and make his armors without difficulty in obtaining water.

Besides Ello, the ironworking activity of the Corte di Casale (Canzo) is also linked to the Missaglia family. The oldest record concerning the Negroni family’s mining activities at Canzo dates back to 1462, when Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, granted the family from Ello permission to extract and work any kind of metal found in the territory of the Canzo community.

Exactly ten years later, Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza sold the entire Casale fiefdom to Antonio Missaglia, also with the aim of promoting the ironworking activities of the ducal gunsmith family.

Find it in Via della Torre, 9, 23848 Ello LC.

Mantegna's Saint George

Andrea Mantegna, Saint George, ca. 1457, tempera on panel, Venice, Gallerie dell'Accademia

In art history, the figure of Saint George is most naturally associated with the chivalric-courtly context. The knightly saint who kills the dragon to save the princess is always depicted wearing a rich and shining armor and, for this reason, has become the patron saint of gunsmiths, fencers, and archers.

In Andrea Mantegna’s work, preserved at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, Saint George is depicted standing, wearing a beautiful armor and holding a broken spear. At his feet lies the dragon, dead, with the tip of the weapon stuck in its jaw.

The saint, slightly turned to the right, and the dragon protrude from the faux marble frame, creating an illusory effect of invasion into the real space. This spatial device connects the work to the artist’s stay in Padua, which ended by 1459. Mantegna trained in Padua at Squarcione’s workshop, where he learned the illusory application of space and the use of rich antiquarian decorativism, visible here in the garland placed at the top of the painting.

The impassive young man, more of a hero than a Christian saint, wears an elegant Italian armor from the mid-15th century. The tones and colors used in the painting emphasize the brightness of the armor, which is in turn accentuated by the bright reds of the military cloak, straps, and belt.

The fortified city in the background, depicted atop a hill crossed by a winding path, represents Selene, under whose walls, according to legend, Saint George killed the dragon.

Find it in Via della Torre, 1, 23848 Ello LC.

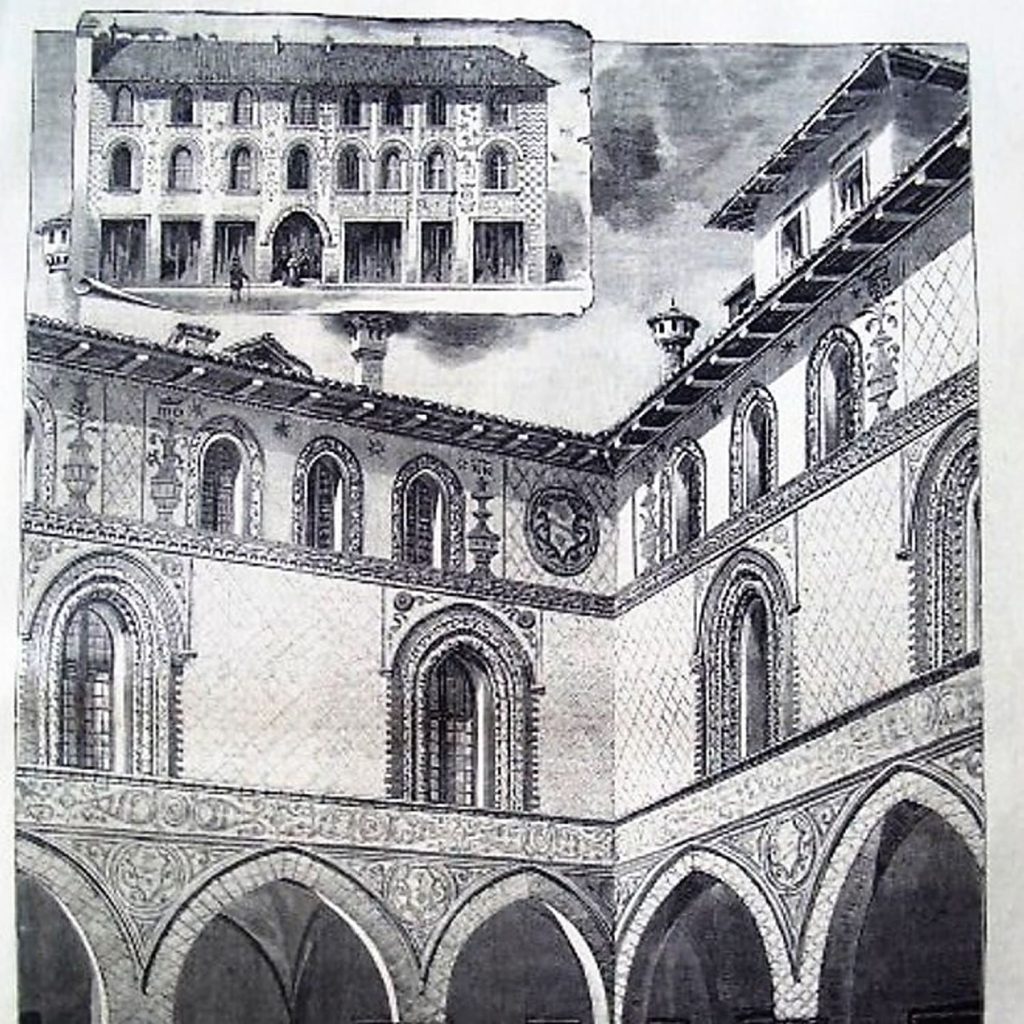

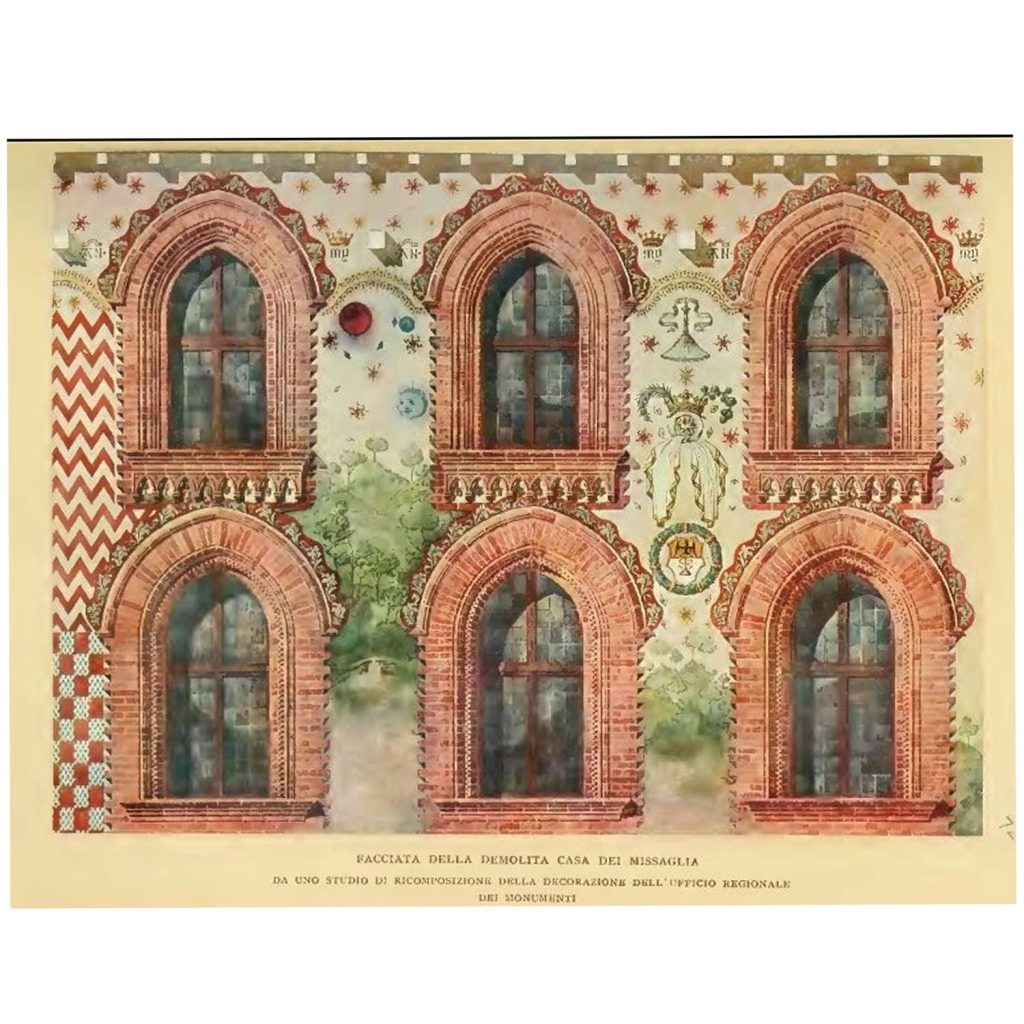

The Houses of the Missaglia

Drawing of Casa Missaglia on Via Spadari in Milan in a Drawing Published in "Il Secolo Illustrato" in 1902

Thanks to the fame and wealth gained during the 15th century, the Negroni family purchased several houses and workshops in Brianza and Milan.

The main and most famous residence of the Missaglia family is the now-destroyed Milanese house on Via Spadari, nicknamed “Casa dell’Inferno,” perhaps due to the impressive spectacle of the forge fires and the deafening sounds of the hammers striking the anvils.

This palace, located just a few steps from Piazza Duomo, was demolished between 1901 and 1902 to meet the requirements of the city’s master plan. What remains of the house and the beautiful 15th-century decoration of the facade is now preserved at the Museum of Ancient Art at the Sforza Castle. The house was one of the most elegant and decorated residences in Milan. In the courtyard, there was a portico marked by arches supported by small pillars with decorated capitals and bas-reliefs bearing the insignia of the Missaglia family. The windows, both inside and outside the courtyard, were pointed, adorned with frames decorated in terracotta, and between one window and another were painted vases with laurel branches and flowers, Sforza emblems, stars and Missaglia monograms, shields, mottos, astrological representations, landscapes, and finally, to demarcate the neighboring buildings, geometric decorations.

Besides this residence, in Milan, they owned a warehouse-house overlooking the castle square at Porta Giovia and a workshop in the Sant’Angelo della Martesana area (Navigli area).

Around the 1470s, to secure a regular supply of raw materials, the Negroni family managed some lands in the Corte di Casale, an area rich in iron near Canzo (CO).

In the village of Ello, the Missaglia family owned a large house that still exists today. In the last three decades of the 15th century, Antonio Negroni decided to enlarge and embellish the family home by acquiring buildings between Via Orientale ai Monti, Via della Torre, and Via Massimo de Vecchi. Even in the 1930s, it was still possible to see the Missaglia monogram engraved on some stones in the village and observe some fresco decoration remains, such as a double portrait in roundels of Antonio Negroni and his wife, depicted on either side of a Christus patiens (Suffering Christ), also frescoed.

Find it here Via della Torre, 1, 23848 Ello LC.

The Missaglia and Galeazzo Maria Sforza

Antonio Missaglia, Steel Armor, ca. 1450, Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum

In 1450, Francesco Sforza became Duke of Milan. This would prove to be the winning card for the definitive revival of the armor economy. Their widespread trade was encouraged by the expansionist and military policy pursued by the new duke.

From the beginning of his duchy, Francesco Sforza turned to the Missaglia family as the primary suppliers of armor, thus beginning a series of important collaborations. The ducal court even exempted Tommaso Missaglia from paying taxes.

Such a privilege proved to be very exclusive, especially considering that it would be renewed by Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza for Antonio, Tommaso’s son.

The Sforza dukes always showed attention to the problems of the Ello family, granting them hammers in privileged areas of Milan or lands in Brianza rich in minerals.

Francesco Sforza’s death in 1466 did not affect the already well-established production of the Missaglia. The new duke, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, left unchanged the privileges previously earned by the Ello family.

Under Antonio Missaglia, the fame and socio-economic well-being of the family greatly increased. The Duke of Milan, who had fallen behind in payments for armor, tried to resolve the issue by granting Antonio and his heirs the fiefdom of Casale (which included Canzo, Caslino d’Erba, Castelmarte, Longone al Segrino, Proserpio, and other territories) and its relative revenues. Thus, in 1472, Antonio became the feudal lord of this area around Erba.

In 1476, Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza was assassinated, and consequently, the regency period of his wife, Bona di Savoia, began since their son, Gian Galeazzo Sforza, was too young to govern.

Even in this case, the change of leadership did not negatively affect the Missaglia’s activity but, on the contrary, led to new commissions and, in 1480, to the consolidation of relations between the ducal chamber and Antonio’s workshop, which officially became the ducal gunsmith.

Find it in the Via Orientale ai Monti, 8, 23848 Ello LC.

Bramante's Men-at-Arms

DONATO BRAMANTE, MAN WITH A BROADSWORD, ca. 1486, FRESCO DETACHED AND TRANSFERRED ONTO CANVAS, MILAN, PINACOTECA DI BRERA

In the Renaissance, the lords of Italian courts and the most powerful condottieri did not display their armors only on battlefields or during clashes with enemies but also loved to be portrayed in such attire in courtly and private contexts.

Armors did not only have a practical function, namely, the primary one of attacking or defending during combat, but they also carried a symbolic value of great importance.

Between the 15th and 16th centuries, there were many depictions of Men-at-Arms and Men of Letters inside private houses, courts, and public palaces. There was a widespread understanding that one could not be a good condottiere without first knowing literature or appreciating art. It was necessary that, besides having a military background, men of power also knew Latin literature, classical rhetoric, and other humanities disciplines.

A significant example of this is Donato Bramante’s work, created towards the late 1480s and now preserved at the Pinacoteca di Brera.

The work is part of the famous Bramante cycle of Men-at-Arms, composed of seven figures larger than life-size. These figures were supposed to be inside the palace of Gaspare Ambrogio Visconti, a poet and man of letters very close to the court of Ludovico il Moro, for whom the Negroni family worked. In this private house, famous for the learned conversations and banquets held within, there was not only a room decorated with trees and others with animals, but also a room called “dei baroni” (of the barons), because it depicted such Men-at-Arms.

In creating the cycle, Bramante would have drawn inspiration from the Ficinian Neoplatonic conception of the hero cult, which required the union of physical strength and spiritual elevation through music and poetry.

However, these are not mythological heroes but contemporary swordsmen, whose names were inscribed in the decoration, now no longer legible.

The cycle, with its modern qualities of perspective layout and psychological depiction of the characters, became an authoritative model between the 15th and 16th centuries, looked up to by other great Lombard artists like Vincenzo Foppa, Bramantino, and the young Zenale.

Find it in the Via Filatoio, 3, 23848 Ello LC.

The Missaglia and Ludovico il Moro

GIOVANNI AMBROGIO DE PREDIS, LUDOVICO IL MORO IN ARMOR, MINIATURE FROM ELIO DONATO'S LATIN GRAMMAR, LATE 15TH CENTURY, TEMPERA ON PARCHMENT, MILAN, BIBLIOTECA TRIVULZIANA

In 1480, Bona of Savoy lost control of the city of Milan due to the ambitions of Ludovico il Moro, the brother of the late Galeazzo Maria Sforza. He managed to remove his sister-in-law and took over the duchy under the pretext of protecting the life of his nephew Gian Galeazzo.

Meanwhile, the fame of the Missaglia family continued to grow, making Antonio not only an armorer but also a wealthy entrepreneur.

By 1496, however, Antonio Missaglia was deceased. He had been the backbone of the family economy for more than thirty years and had made good use of the inheritance of assets and knowledge he had received from his father, Tommaso. Unfortunately, the heirs could not match Antonio’s skills and economic initiative. From producers and investors, they returned to being mere traders, eventually leaving increasingly faint historical traces.

A document from 1504 marked a clear passing of the torch, which went from the Missaglia to a new family of armorers: the Barini, better known as Negroli. Regarding this family, it is unclear whether they were also originally from Ello or natives of Milan. However, aside from these historical uncertainties, the significant aspect is the implosion of the Missaglia family.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the Missaglia family could no longer complete their work, became indebted, and some members ended up in jail precisely for not meeting several commissions within the established deadlines.

Starting from nothing, the Missaglia family reached the pinnacle of their evolutionary journey thanks to Tommaso’s perseverance and Antonio’s technical and commercial abilities. After his death, the spirit of economic initiative and dedication to technological and artisanal innovation—on which the Missaglia family’s wealth and important European clientele depended—faded away.

Find it in Via M. de Vecchi, 2, 23848 Ello LC.

The Brera Altarpiece by Piero della Francesca

Piero della Francesca, Detail of the Madonna and Child with Saints, Angels, and Federico da Montefeltro (Brera Altarpiece or San Bernardino Altarpiece), ca. 1472-74, Tempera on Panel, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

The city of Urbino and the figure of Duke Federico da Montefeltro played a fundamental role in 15th-century Italian history and art.

The city’s Ducal Palace is one of the masterpieces of Renaissance architecture. Inside is the duke’s small and partially preserved studiolo (1473-77). It is a room featuring portraits of famous individuals and wood inlay decoration. The idea behind the depictions is to represent the arts of the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy), disciplines considered fundamental to the education of the ruler and the entire court.

Montefeltro distinguished himself in his life as both an important military captain and a great enthusiast of literature and art. The Lord of Urbino loved to portray himself as the “wise prince” capable of dedicating himself both to the art of war and to study.

The attitude of combining otium and negotium, assumed by Federico, can also be found in other Italian courts, such as Milan. The cultural affinity between Urbino and the Lombard capital has often led critics to compare the Urbino context to that of Milan and, in particular, to see a direct connection between Bramante’s figures at Casa Visconti and the ducal studiolo.

A particularly famous portrait that well embodies the duke’s character is visible in the Montefeltro Altarpiece by Piero della Francesca (1472-74). The altarpiece, probably made for the church of San Bernardino in Urbino, has been housed at the Pinacoteca di Brera since 1811.

The iconography is that of the Sacred Conversation: in the center is the Virgin on the throne holding the sleeping Child; surrounding her are, from the left, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Bernardino, Saint Jerome, Saint Francis, Saint Peter Martyr, and Saint John the Evangelist. Behind the Madonna are the archangels, and kneeling in front of the group is Federico da Montefeltro dressed as a condottiero.

The duke wears full armor, including a sword and cloak. On the ground are the helmet, the staff of command, and parts of the armor, removed so the duke could clasp his hands in prayer. The armor is similar, in some respects, to the Milanese style, but it is difficult to identify a possible workshop of manufacture.

Find it in Via M. de Vecchi, 2, 23848 Ello LC.

The Various Renaissance Armors

GIOVANNI MARCO MERAVIGLIA AND DAMIANO MISSAGLIA, ARMOR OF CLAUDE DE VAUDREY, ca. 1495, VIENNA, KUNSTHISTORISCHES MUSEUM

The steel armor was created around the mid-14th century. Although it’s a defensive tool used worldwide, the earliest known armors are Italian.

Between 1420 and around 1480, the armors of the Italian Peninsula were particularly appreciated, as Italian armorers tended to make the shapes more rounded and free of exaggerations. One can indeed observe a tendency to soften and refine the body’s shapes, which are hidden beneath heavy layers of metal.

The manufacturing of armors goes hand in hand with the development of metallurgy, which reached significant levels towards the end of the 14th century. This technical advancement allowed for meeting the increasing demands of weaponry and condottieri.

The creation of an armor involves many armorers, masters, and artisans, each with their own specialization. However, most armor makers did not venture beyond limited local commerce. One of the exceptions was the Negroni family, who, with their “dynasty,” achieved extremely high levels of wealth and fame.

Between 1480 and 1530, a period of great wars and geopolitical changes, the concept of defensive weapons changed significantly. Warfare itself transformed, from battles where cavalry was the main element to battles dominated by infantry.

An example of armor designed for combat on foot is the one made for Claude de Vaudrey, Lord of L’Aigle and Chilly and chamberlain of Duke Charles of Burgundy.

According to sources, the armor was won by Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg following a duel with the Burgundian chamberlain at the Imperial Diet in Worms (1495).

It was made by two very important Milanese workshops: that of the Meraviglia and that of the Missaglia. Damiano Missaglia, nephew of the more famous Antonio, likely made a production agreement with the Meraviglia for the execution of this armor.

This armor stands out for its rotating skirt, offering maximum protection for the legs while allowing significant mobility. In its shapes and manufacture, one can see a style that seeks to combine the French taste of the patron with the Milanese taste of the armorers.

The Missaglia Armors in Mantua

ANTONIO MISSAGLIA, GIOVANNI ANTONIO DELLE FIBBIE, ANTONIO DE OSMA?, AND OTHER MASTERS, COMPOSITE ARMOR FOR MAN-AT-ARMS, ca. 1470-90, MANTUA, DIOCESAN MUSEUM

The works of the Negroni family are preserved in collections, armories, and museums worldwide, but one of the most important collections of their armors is found in Italy, particularly in Mantua.

In the second half of the 15th century, several armorers were documented in Mantua: Zoan Pietro da Milano, Michieletto delle Corazzine, Jacopo da Capua, and others. The Gonzaga, lords of Mantua, in addition to local production, had in their service the finest weapon and armor makers in Europe: from the da Merate brothers to the Helmschmied, and the Negroni, known as Missaglia.

The latter were the creators of six of the twelve composite armors in the Italian Gothic style from the Sanctuary of Madonna delle Grazie in Curtatone, about nine kilometers from Mantua. To date, this is the most important collection of defensive armor in the world.

The history of these armors is unique and complicated: they left the ducal armory along with others to be delivered to the Sanctuary in a special operation to decorate the nave. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the armors were combined with papier-mâché and other materials to form a long series of life-size mannequins placed inside a wooden structure located at the clerestory level of the church.

Today, thanks to the detailed study of Sir James Gow Mann, director of the Wallace Collection in London in the 1930s, the armors have been cleaned of additions and are now displayed at the Francesco Gonzaga Diocesan Museum in Mantua.